A labyrinthine collection of female

images in various photographic styles does not quite capture

Matuschka's autobiographical retrospective. The walls of the pocket

Sohn Fine Art Gallery pack iconic photos across the 40-year span of her

career. Light filters from the picture windows and the open door into

the two white rooms, lending a clinical feel to the place. Tucked

into a corner next to some jewelry cases hangs the famous Beauty out of Damage, as though it were just another photograph in the

series, one amongst her many important works.

Looking back at these highlights from

her career, it becomes apparent that Matuschka's portraiture begins

to show agency, only after she gained notoriety for the photograph of

her breast cancer scar. In so many of her photos, her self-image is

passive. Even in Beauty out of Damage, the artist's face is

turned away from the camera, as though she hides from both the

camera's gaze and her wounding. As cover of the New York Times

Sunday Magazine, the somber image becomes a political statement,

and its critical reception read the image as representing “agency.”

Although a passive positioning of the body, Matuschka's image

ironically shifts from her identity as model, photography assistant,

and object, to one that actively expresses with the intent to raise

cancer awareness.

I remember my own encounter with that

photograph, its strange androgyny teetering the line between

classical art and pornography. As a young adult, I felt ashamed of

looking at the image, wanting to turn away. The fine white dress,

tailored to fit her body with one side cut away, underscores the

missing breast and hideous gash of a scar. Her ultra-thin body could

have been a young man's: a missing aureole, the ribcage taught. Her

hair bound in a white sash heightened the ambiguity. Blurring the

lines of male and female, her turned face seemed to convey the very

shame I felt. To maintain power and movement within society one must

uphold the hegemonic norms represented by clearly defined gender

roles. I understood clearly the image's power of questioning what

constitutes the larger categories of “woman,” “female,” and

“femininity.” Questioning the norms was not only shameful but

also dangerous.

Just coming into my own womanhood at

sixteen, I knew the seductiveness as well as the burden of femaleness

wrapped up in societal projections represented by the breast. I hated

the neighborhood workmen catcalling to me as I walked past them. As a

girl, I had wanted to be a boy, to be a dancer, to play lacrosse, and

these breasts and the definitions of girl and female limited me not

only physically but also socially. My mother dressed me in boy

play-clothes except on Sundays when I wore stiff dresses for church.

I neither fit in with the boys nor with the girls: the boys teased me

with the moniker “Tomboy,” and the girls shunned me from their

bathroom make-up sessions and gossip. Not to lapse into any kind of

self-pity, this portrait is meant simply to give you a sense that I

could identify with this image in a very poignant and non-dismissive

way.

Matuschka's photographs speak to me of

some of these issues. I see a young woman who struggled to conceive

of herself as an artist in a male-dominated profession at the same

time trying to make money as a model and an artist. In her early

work, there is a tension between intimacy and exposure that appears

to castigate the self. I feel compassion for this young photographer

who takes her own body, which others have used for its object-value

of classical Western beauty and expressiveness, and explores and

investigates her body from a detached photographer-like perspective.

I find it difficult to see the agency in using herself in this way,

and see it rather as an expression of what modeling can do to the

psyche. The photographs mitigate a conflict between seduction and

authenticity as expressions of power. And the difficulty of woman

developing her own artistic perspective from within the confines of

societal definitions of “woman.”

I will begin this discussion by way of

a poem by Anne Sexton. “Barefoot,” from her collection Love

Poems, tells the tale of a morning between the speaker and her

lover on holiday at the beach:

Loving me with my shoes off

means loving my long brown legs,

sweet dears, as good as spoons;

and my feet, those two children

let out to play naked. Intricate nubs,

my toes. No longer body.

Immediately, the speaker focuses on her

body as an object of love and desire from an exterior perspective.

She moves up her legs from one body part to another with a kind of

innocence mixed with seduction. The reader is likewise encouraged to

observe her like an eye moving across her body focusing on certain

body parts disconnected from the rest.

And what's more, see toenails and

prehensile joints of joints and

all ten stages, root by root.

All spirited and wild, this little

piggy went to market and this little

piggy

stayed. Long brown legs and long brown

toes.

The observation is child-like and

harkens to a time of childhood games. Her image is synonymous with "nature," a

classic metaphor for woman: toes are like the roots of a plant. In

the following lines, with the introduction of the listener, the

speaker's tone changes to one of seduction, predicated on mystery and

secrecy.

Further up, my darling, the woman

is calling her secrets, little houses,

little tongues that tell you.

Perhaps a euphemism for the woman's

sexual parts...The relationship becomes clearer as the poem

progresses.

There is no one else but us

in this house on the land spit.

The sea wears a bell in its navel.

And I'm your barefoot wench for a

whole week. Do you care for salami?

No. You'd rather not have a scotch?

No. You really don't drink. You do

drink me.

The sexual division of labor

represented in these lines is quite classic: Sexton's speaker claims

the essential role and function of the submissive lover, a “wench”

as she calls it, serving him imaginary food, with her body ultimately

ending up as that food. Through this conventional love-relationship,

the speaker offers her body up for the listener to imbibe. The reader

too can experience “woman” in this way.

The gulls kill fish,

crying out like three-year-olds.

I am, I am, I am

all night long.

Barefoot,

I drum up and down

your back

In the morning I

run from door to door

of the

cabin playing chase me.

Now you grab me by

the ankles.

Now you work your

way up the legs

and come to pierce

me at my hunger mark.

Sexton conflates the mature acts of sex

and the hunt with childhood play. The gulls when they kill sound like

children at play, and the listener of the poem chases the speaker as

in child's play and “pierces” her, clearly a reference to sexual

intercourse. But her identity too is wrapped up in the play. She

cries out “I am” three times as though clamoring for

self-assertiveness. While the speaker may be the metaphoric food of

the poem and a sexualized object, her body too feels “hunger” or

desire for sex. She finds sexual expression in being the object of

the hunt and power in being sexualized, and looked at, pursued.

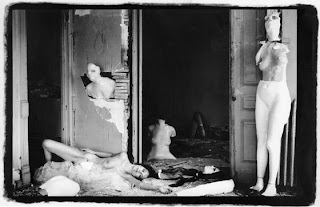

In Matuschka's work, I am drawn to

“Doll House” (1987), a photograph from her Ruins series,

developed on the occasion of a song she wrote for her band “The

Ruins.” The song details a failed love relationship which neglected

to account for the “ruins.” A black and

white still, the artist appears amongst gauze papier mache and

mannequin body parts, suggesting cast off parts of the self that are

hollow and disembodied. Her face is expressionless, almost

emotionless like a doll waiting to be played with or just having been

cast aside, already played with. The body parts are fragmented but

also sexualized. Once pursued, the character in this photo is now

alone, one of the many aspects of ruination in the house. Whereas the

house represents the mind, these multiple and disparate selves are

always already caught in the act of being cast off: in this doll

house, the “dolls” are strewn about the decrepit rooms, unengaged

in the play, and unaware of their complicity in the process. The

dolls are acted-upon, created of multiple variants of the female

body. A fishnet-clad leg hidden in the interior-most room is

mysterious, seductive, but to access that self, one must walk over

the deflated chest and face-mask of another self, laid out

corpse-like in the doorway.

|

| Doll House (1987), Matuschka |

Her work holds similar thematic

connection to Cindy Sherman, another New York-based artist working at

the time she was living and working in New York. Not only are the

seemingly auto-biographical photo-plays of the female artist a

similar strategy in their work, but also are the questions that

surface in their photography around “woman” and “femaleness.”

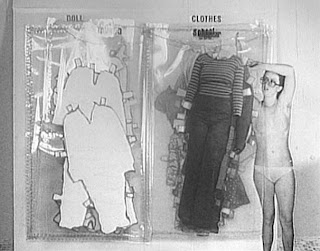

Sherman's “Doll Clothes” (1975) echoes this preoccupation with

the female as a model who is dressed up either to be played with or

to be playing a role:

|

| Doll Clothes (1975), Cindy Sherman |

Both Matuschka's and Sherman's

biographies include the professional title Model: a body to be looked

at and photographed by others. However, in Sherman's work, clearly

the artist is the agent of her profession, actively pulling at the

clothing she will wear. She is no naked muse. Her career suggests

this trajectory, as she dresses up in various roles calling viewers

to question preconceived notions, myths, fables, values, or held

beliefs about society and culture. Matuschka's career had a different

path. In a May 2013 interview with Charles Guiliano, she tells:

“The great story is how I got into

photography in the first place. I was with friends skinny dipping in

a pond when I was about 16. A Hell’s Angels type group of

motorcyclists came and we all jumped into the water. It turns out

instead of Harleys they rode Hondas. A guy came up with a camera and

asked if he could take a few photographs. I said yes under one

condition can you send them to us? I posed with my hippy friends and

I stood out like a statue. Once they saw the photographs everyone

wanted to photograph me. I posed and learned to print before I took

my first picture. I became a darkroom assistant to the photographers

photographing me.”

Modeling became a way for her to

support herself, educate herself, and to maintain ties in the art

world.

One shockingly similar photograph

appears in both of their collections: that of the dead woman.

Sherman's Untitled 153 (1985), which appeared in Time

Magazine's best world photographs from 1980-1990, and Matuschka's

Framed (1988) from her Ruins

series. In both pictures, the dead women are hollow-eyed, cast off

into the natural landscape. Their bodies call out for the the viewer

to create a narrative around them. Sherman's body is covered in dirt

as though her dead body blends into the mossy landscape. Matuschka's

dead body appears to have either broken through or been shoved

through an artist's canvas; she is wrapped up in plastic film and a

fragmented, gauze body part lies at her side. But the viewer knows

these are images of the artist who is obviously not dead, but rather

playing the role of a young woman who has been murdered. The cultural

reception of Untitled 153

as well as Beauty out of Damage

underscores a societal preoccupation with the maimed or dead female

body.

|

| Untitled 153 (1985). Cindy Sherman |

Sherman's

Untitled 153 operates

on the level of myth and fable, while Matuschka's Framed

operates on the level of a

construction, a meta-textual conception of the artist within the

confines of the art world. Sherman is framed within the photo, her

body emerging off the image somewhere off camera, but Matschuka's

body is fully shown, framed inside a frame. Both images suggest

something about the dead woman, the ideology of the quiet, passive,

cast off body of woman with which the woman artist must contend in

order to create her own work. Helene Cixous writes: “We need a dead

woman to begin.” The artist must confront the passive in order to

gain agency, in order to become active, initiating into the masculine

art world. However, even as the photographer's body breaks through

the conventional canvas in Framed,

she is still a painted object of desire, packaged, wrapped up,

constrained, lifeless.

A few of Matuschka's cartoon drawings

reveal this struggle within the modeling industry and in the art

world. To be a female artist and model is to confront the sexism

therein as well as to play the various roles that others desire to

photograph.

Their pioneering efforts in breaking

through the gender barrier in art, while different, offer viewers a

way of understanding the ways in which the woman artist must confront

the ideological limitations of “woman” as well as her own

complicit relationship within the social power dynamic. Their early

work, the focus of this article, was largely influential for

appearing to reflect the accepted ideological norms; however, with

that positive reception their careers shifted and solidified, and

their work can be viewed as important as it also resists those norms,

interrogating “woman” and later “gender” and “cultural

identity” as a social constructions.

Matuschka's A Body Biography, a

40-year retrospective of her autobiographical photographs, is

currently on display at Sohn Fine Art in Stockbridge, Mass from now

until July 1, 2013.

Cindy Sherman's 35-year retrospective

through MoMA is currently on display at the Dallas Museum of Art.

Sources:

Matuschka's website: http://matuschka.net/homepage.html#photo

Cindy Sherman's interactive exhibition on the MoMA website: http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2012/cindysherman/about-the-exhibition/

Guiliano, Charles. "Matuschka Maimed, Claimed, and Famed: A Life and Career Defined by an Iconic Image." www.berkshirefinearts.com

Sexton, Anne. Love Poems. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1989.

No comments:

Post a Comment